Psoriatic Arthritis (PA) – A More in Depth Look

Psoriasis is a miserable skin condition caused by abnormal cell growth. Why it happens isn’t clear, but immune, genetic, and environmental factors, such as bacterial infections, seem to play a role. The results are flaking skin, itchy red lesions, and sometimes yellow-white scales as the disease progresses on various parts of the body, especially the scalp, the back of the elbows, knees, umbilicus (belly button), and genitals. It can also appear as flaking skin between the toes, leading some people to dismiss it (or attempt to treat it) as athlete’s foot. It affects from two to four per cent of the white population (far fewer blacks are affected), and it has one nasty wrinkle: Some people with psoriasis —five to ten per cent—also develop arthritis.

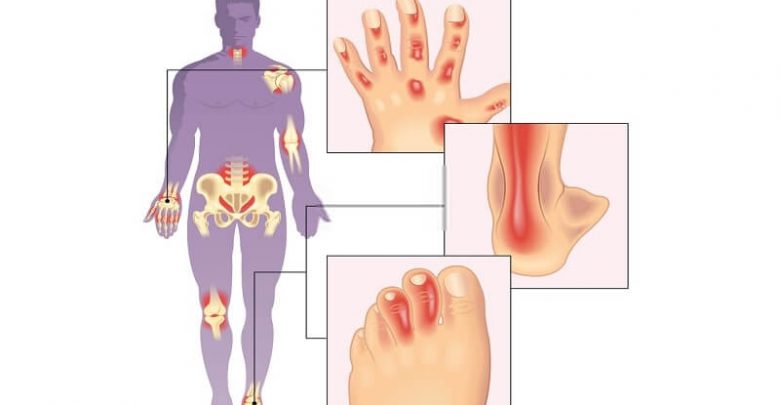

In fact, in psoriatic arthritis, arthritic symptoms usually develop first, with the skin condition trailing by months, even years in some cases. PA is gender-neutral, affecting men and women equally. It’s rare to see it in children under thirteen; the usual age of onset is between thirty and fifty. Nearly all PA sufferers (about 95 per cent) have peripheral joint involvement; the remainder have exclusive spinal involvement, though 20 to 40 per cent of patients have both. In some people, inflammation may develop in the periosteum (a blood-laced membrane that surrounds and nourishes bones), in tendons, and the points where tendons attach to bone (enthesopathy). Others are only affected in the end joints of fingers and toes; finger- and toenails may develop pitting or ridges; and inflammation and swelling of the flexor tendons can cause fingers to take on a characteristic “sausage digit” appearance.

Clinically PA may resemble both Reiter’s syndrome and RA; a diagnosis of PA is only confirmed with evidence of skin or nail changes typical of the condition. The systemic component of PA, though, is generally limited to eye inflammation (such as iritis, episcleritis, or conjunctivitis).

Treatment consists of the same regimens used for other inflammatory conditions—ASA and NSAIDs for mild to moderate cases, for example. For more intractable cases, DMARDs (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs) may be prescribed, including gold, chloroquine, and methotrexate; antimalarials, such as sulfasalazine, are effective for some people, and soft-tissue involvement may be treated with corticosteroid injections. Suppressing the skin disease (with topical skin creams and corticosteroids) is sometimes helpful in controlling the arthritic aspect of PA; where the psoriasis proves especially recalcitrant, a dermatologist may be called on for further treatment.

Education is a big part of treatment to ensure that patients understand and practise joint protection, do regular joint exercises to maintain maximum range of motion, and use splints where necessary. A minority of people with PA suffer long-term problems and joint destruction, but most cases of psoriatic arthritis are mild, and most patients—probably 80 per cent—do quite well.