Information about Scoliosis Brace

For over two thousand years, doctors have attempted to support, correct, or halt scoliosis through the use of external mechanical means. The ancient Greek physician Hippocrates used what he called a “forcible reduction apparatus” to attempt to correct scoliotic curves. In subsequent centuries, doctors tried tightly wrapping scoliosis patients in bandages that held rigid splints in place, imprisoning patients’ backs and chests in hinged metal shells, and encasing entire upper bodies in plaster casts. Though the modern brace has thoroughly refined and modified the ancient technique, the principles that underlie brace treatment remain the same as those set down by Hippocrates.

How Braces Work ?

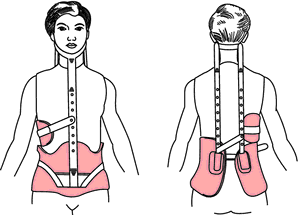

Although braces cannot permanently correct a curve, they can stop the progression of a curve. Simple mechanical means straighten a scoliotic curve while it is in a brace. Pads held in place by the brace apply external pressure below the apex of the curve. These pads push on the spine, forcing it into a straighter position. The Milwaukee brace, designed by Dr. Walter Blount and Dr. Albert Schmidt in the 1940s, ushered in the modern era of brace treatment. It uses a neck ring and pelvic mold to provide traction as well. It was hoped that this “spinal tug-of-war”—pulling the upper and lower ends of the spine in opposite directions—would straighten the spine even further.

Milwaukee braces were once thought to both act on the passive body and stimulate active forces in the patient. Children were taught exercises to perform in their braces to pull away from the pads. Doctors would instruct children to try to be tall in the brace, to lift themselves up so that their necks rose above the neck ring. It was hoped that the combination of the brace and these exercises would stimulate and train the muscles of the upper body to pull against the curve and keep the spine straighter even after the brace was removed. Recent studies, however, have demonstrated that no increase occurred in the activity of trunk muscles owing to the bracing. Attempts to spur the patient’s back muscles into taking action have little impact on the curve’s size and shape.

The constant application of force provided by the pads on a brace usually results in apparent curve correction, but this correction does not generally last. After the brace is removed, curves tend to gradually return to their original shape and magnitude. Most scoliosis patients who receive successful brace treatment thus end up no better than they began—but most end up no worse either than when they started. And that is important because the aim of bracing is not to provide permanent correction but merely to stop the progression of the curve.

Who Should Get Braced ?

Not everyone with idiopathic scoliosis is a viable candidate for bracing. The appropriateness of brace treatment depends on the individual’s skeletal maturity, the size and location of the curve, and the patient’s willingness to wear the brace in compliance with the doctor’s instructions.

Skeletal Maturity

In general, people are candidates for bracing only if they still have at least eighteen months of growth remaining. Therefore, only juveniles and adolescents should receive brace treatment for their scoliosis. A child might begin brace treatment even before he begins walking, beginning with a plaster jacket and then moving up to bracing as the infant becomes a toddler. Although such an intervention is rare, some children are braced from early childhood. At the other end of childhood, if an adolescent has less than a year of growth remaining, bracing would serve little or no purpose. Since bracing is intended to halt curve progression during growth spurts, teenagers whose growth has already begun to slow would derive little benefit from a brace.

Adults have no skeletal growth remaining and should therefore not receive brace treatment to halt the progression of their scoliosis. I do, however, sometimes prescribe a brace for older adults who suffer from severe pain but have reached an age that eliminates surgery as an option. Surgery may pose too many dangers for, say, a seventyfive- year-old woman who complains of constant and severe pain from her scoliosis, her deformity, and arthritis. In such a case, an external brace can often relieve pain simply by providing the patient with extra back support.

Curve Size

In general, a child who has a curve less than 25 degrees needs no intervention. Most orthopedists agree that children with curves that measure less than 20 degrees require no treatment at all, while curves between 20 and 29 degrees warrant further observation (every four to six months) to document any progression. Bracing is appropriate if the person’s curve measures between 30 and 40 degrees. If, however, a curve has progressed more than 5 to 10 degrees, bracing might be warranted at a smaller magnitude. I would probably recommend bracing for a 25-degree curve, for example, if documented progression exists.

In general, a child who has a curve less than 25 degrees needs no intervention. Most orthopedists agree that children with curves that measure less than 20 degrees require no treatment at all, while curves between 20 and 29 degrees warrant further observation (every four to six months) to document any progression. Bracing is appropriate if the person’s curve measures between 30 and 40 degrees. If, however, a curve has progressed more than 5 to 10 degrees, bracing might be warranted at a smaller magnitude. I would probably recommend bracing for a 25-degree curve, for example, if documented progression exists.

Curves that exceed 40 degrees prove much less amenable to brace treatment. One study found a 50 percent rate of failure (meaning that the curve progressed despite bracing) among patients who had curves greater than 40 degrees and were treated through bracing. Consequently, patients with curves of this magnitude must, with their doctors and parents, decide whether braces or surgery seems most appropriate. In the case of a twelve-year-old girl who has not yet menstruated and who has a 40-degree curve, I would inform her and her parents that although bracing is an option, braces fail to check the progression of curves of that magnitude 50 percent of the time. Some families will still opt for bracing, preferring to see what happens and wait to schedule surgery only if the curve worsens; others will immediately choose surgery. Either choice is reasonable.

Although skeletal maturity and curve size serve as useful guidelines in determining who might be an appropriate candidate for brace treatment, they are not absolutely reliable criteria, and gray areas exist. Indications become more difficult to define as a child becomes more skeletally mature. If a child had a 35-degree curve and X-rays showed a Risser sign of 4, I would probably not brace that child. Since the child would have already virtually achieved skeletal maturity, a brace probably would not accomplish much. If the child had a Risser sign of 3 and had just had her first menstrual period, however, I might recommend bracing.

Other cases may seem to contradict these guidelines. Suppose an eight-year-old child had a 40-degree curve. Although a curve of this size is treated effectively with bracing only half the time statistically, no one wants to operate on an eight-year-old. Sometimes the nature of a particular curve and its natural history will dictate the need for surgery, however, even on a young patient. In this case, I would recommend putting the child in a full-time brace, but I would let the child’s parents know that this strategy will almost certainly only buy some time, allowing the child to mature and the spine to grow more prior to surgery. It might halt progression for a short time, but the strong likelihood of progression, regardless of bracing, suggests the need for surgery when the child is older. If bracing fails, however, surgery would be an appropriate choice even for a young child.

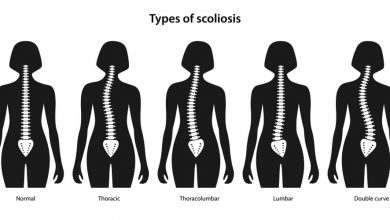

Curve Location

Given that the patient’s skeletal maturity and curve size warrant brace treatment, most types of scoliotic curves respond well to bracing—but not all do. A left thoracic curve with an apex higher than T5 or T4 as well as cervicothoracic curves, which are very rare, cannot be braced effectively. In the past, orthopedists and orthotists (manufacturers of braces) attempted to control these high curves through various shoulder slings and straps attached to a Milwaukee brace. But the apex of a high thoracic or cervicothoracic curve is so high that even such attachments provided little mechanical advantage. Since high curves of this kind also tend to be more cosmetically deforming than most lower curves, orthopedists tend to treat them surgically at a lesser magnitude than they would lower curves.

Compliance

The patient’s willingness to wear the brace plays a critical role in determining whether bracing is appropriate. Some kids simply will not wear a brace, regardless of whether it is a full Milwaukee brace or the more diserect underarm brace. “I wore a Milwaukee brace from the age of fourteen to sixteen,” Rachel recalls, “and then I stopped wearing it just because I was starting high school and I just wasn’t going to wear that thing to high school.” Understandably, during this critical period of identity formation, adolescents don’t like anything that sets them apart from their peers. And a brace, especially the bulky, hard-to-hide Milwaukee brace, can promote feelings of isolation and estrangement.

Clearly, the orthopedist, the child, and the parents must consider the psychological and emotional impairment that braces can cause among teenagers. For instance, if I have recommended a brace for a thirteen-year-old with a 30-degree curve and the child repeatedly insists that the brace would make him so miserable and unhappy that he’d refuse to wear it, I probably won’t prescribe one. If the child will not waver from this refusal, I eventually tell parents that no matter how tough they are, they can’t make the child wear the brace. I do not believe the physician should serve as the patient’s police officer. Compliance with the bracing schedule ought to be a shared responsibility among the physician, family, and patient. I try hard to get patients to wear their braces through education rather than intimidation. But if a patient shows no sign of compliance, it becomes necessary to forgo the brace and go back to observing the natural history of the curve, that is, what happens to the untreated curve. If the curve gets worse, then it gets worse. And ultimately, the curve may reach a magnitude that necessitates surgery.

Other factors are part of decisions regarding the appropriateness of bracing. Susan remembers that her own history of progressive scoliosis had an impact on the treatment of her daughter’s scoliosis. “If I hadn’t had scoliosis as a child, the doctor I went to would have never put my daughter in a brace because her curve wasn’t that bad.” A family history of scoliosis does play a part in determining appropriate treatment. In other words, 1 might treat a child with such a history more aggressively than I would a child who had no family history of scoliosis. Indeed, having had personal experience of scoliosis, the parents of such children often request more aggressive interventions.

Another important consideration involves the patient’s and family’s feelings regarding the cosmetic deformity caused by the curve. Since brace treatment aims primarily to stop progression rather than to correct the curve that already exists, the patient must feel reasonably satisfied with the way she looks for bracing to be appropriate. Bracing will not permanently straighten a scoliotic spine, nor will it make a sizable rib hump go away. So if a patient already feels so uncomfortable or displeased with her looks that she will likely choose to have surgery at a later date, bracing makes little sense.